Header image source: Warrington & Co (with permission)

Introduction

In part one of a series, this article reviews the development of 3D models as public consultation tools. No longer confined to the realms of the gaming industry, 3D models and visualisations have been applied to other areas of daily life. One such area is Urban Planning.

In this article we look at how the traditional tools of public consultations are supplemented by tools which fully immerse users into understanding changes being made in their environment. This article will conclude with the limitations of using 3D Models in public consultations and the advantages comes from using such a tool.

Public Consultations

Public Consultations is an essential to planning processes in the United Kingdom and has a unique role of everyday democracy that reflects the Country’s heritage. Public Consultations are a statutory requirement in the United Kingdom’s Planning Policy, and so architects, developers and planners initiate public engagement.

Public consultations give communities the opportunity to engage with the project team (architects/developers) about the future of the area. This is then used as feedback for Architects who will return to the project development, and make changes that better reflect the projects future environment.

For public engagement to be successful it must:

Public Consultations ideally inspires conversations through an interactive (but not exactly technical) method. The project team then reflects this engagement in the technical detail that often happens in the background.

This engagement with the public is carefully managed to align discussion points at the right time in the design process of a project. This is meant to coincide with the exact roadmap of the project development, while it should be completed prior to construction better practice will have developments engage with the public at its Concept Stage (see RIBA 2020.)

This is not always explained fully to the public and therefore obvious constraints within the design process are not always immediately clear to members of the public. An effective public consultation will present a transparent narrative for members of the public. This will feed into a better overall relationship with the public and become essential to the developer’s future external stakeholder management.

Traditional Methods for Public Engagement

Public Consultations currently use a large arrangement of different methods (emails, letters, social media, and news outlets.) The typical call to action incorporates a public exhibition where the design team presents their vision of the proposals to the public. As engagement becomes more digital, planners and architects have turned to more online tools for presentation and feedback via websites, survey forms, and closed questions.

IA survey recently conducted by Northumbria University on behalf of PlaceChangers on current engagement practices demonstrates the ‘state of the art’ in the industry at present (see below). 115 respondents from within the AEC industry noted in-person public events, social media, websites, and emails as predominant methods for engaging.

Method | % of respondents (115 respondents) |

|---|---|

In person / public event and exhibition | 18% |

Social media | 19% |

Online via website | 18% |

A third party platform | 10% |

Telephone calls | 10% |

Emails | 17% |

Questionnaires / Surveys | 7% |

Physical Engagement via public events and exhibitions usually involve the project team presenting the modelled elements of the architectural design to the community stakeholders. Additional information is provided through boards/posters that demonstrate further data on the wider area relevant to the design (see below). Planners and architects will guide stakeholders at these events through the ideas and scope of the design. They will then gauge the public’s views as participants are invited to leave comments on forms. Naturally 3D models feature in many of those presentations, as for example, for Lancaster’s city centre vision below:

Boards at town centre vision consultation for the Lancaster City Centre (2018).

What is a 3D Model?

With the current changes in the social and technical environment there is a growing adoption of 3D modelling. This runs in parallel with a greater awareness of the need for design quality, for instance, in the UK’s new White Paper on Planning for the Future.

3D models are a 3-dimensional visualisation of the environment. This can be achieved in various ways (see other blog in series) but all revolve around an interactive cartography of an area. This has become more enticing for developers and local authorities as long-term planning simulations become affordable.

The incentive to use an interactive model in a public consultation, is to help stakeholders see and understand the urban landscape, and branch over certain ideas without professional training on the part of the public. It is hoped that such a project encourages further public engagement.

As developers are pulled into the public eye through the likes of social media, the importance of stakeholder management increases and so, their relationships with external stakeholders. They are moving beyond singular engagement events and beginning to engage an on-going interactive method. Digital models are becoming key towards effective communication and public engagement that brings out insights that can improve the project with positive changes relevant to all engaged parties.

Case Study: Warrington Master Plan

As part of the recent regeneration plans of Warrington, a computer-generated 3D model of the area was designed to show how proposed town regeneration schemes would look after development. This would actively work as an interactive Master plan and help planners, architects, designers (and investors) to understand the environmental impact of a prospective building. This was developed in association with AECOM, as part of their asset advisory services.

3D model such as this allow designers to test the core principles to help understand form, function and environmental sustainability, by placing external models into the city model for review. For members of the public, models help proposed works or new developments to be visualised, communicated and its impact assessed on the urban environment.

In a recent public consultation the model was used to exemplify the height of certain buildings in the area. Models such as this demonstrate new proposals scale in context of the environment, helping to see and consider visual impacts more easily.

Warrington Master Plan and model. Source: Warrington & Co (used with permission)

Case Study: 3D pre-app consultation for infill development

PlaceChangers is pioneering the use of 3D building models in consultations. Megan Doherty's project research has show that 3D models help participants understand scale and placement more easily and have greater comfort in their views.

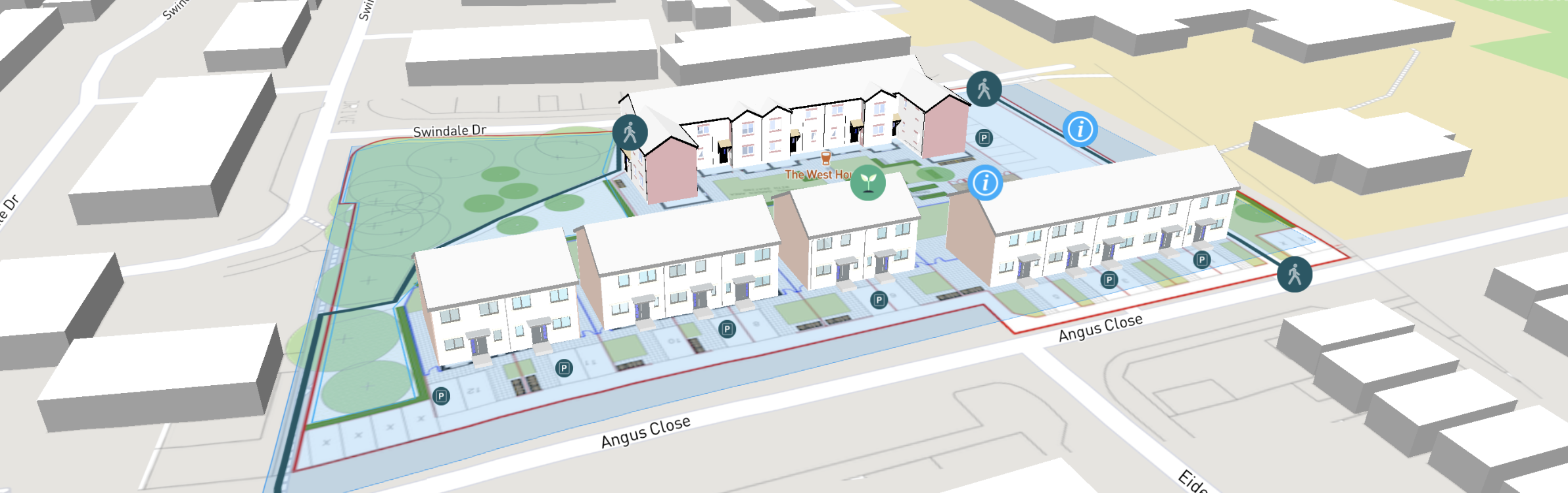

North Tyneside Council ran a 3D consultation for Swindale Drive, a small in-fill development, as part of on-going regeneration efforts. House type models and various other props were used to enable an interactive consultation experience.

Find out more here: 3D proposal maps drive planning consultation for North Tyneside Council

Swindale Drive Consultation. Source: PlaceChangers

Limitations of 3D Model

It is often hard to direct the focus of the public to design details at the best of times, but the 3D model can often be noted as either distracting or overly focused in the wrong areas. It is hard to mediate a public consultation when using digital media, as the information transaction often feels one way.

In the example stated above, Warrington’s use of a 3D model drew attention to the Councils designs of a proposed hotel and flats. Due to its height and its proximity to the centre of the town this was brought up as a major issue to the master plan, although this had been stated in earlier regeneration plans published by the Council.

The production of visual geometric plans is tied to the production of the project development, and it can be hard to accurately portray the current architectural design to the public, especially through a 3D Model. For instance, Warrington’s model, while spatially accurate, presented the design as a dense geometric shape. This meant although when paired with the master plan, the public could observe the designs use of materials that would soften its aesthetic and allow through more light – unfortunately its height and texture meant that its design was misread by the public.

Dense 3D models can be attributed to the shrinking timeline of a project’s development. Though architectural agencies are expanding in their workforces skill-set, the limitation of architects with these skill sets can slow down the production and this can work against the project's timeline. The concept stage (see RIBA 2020) will specifically undertake design reviews with client and project stakeholders. However, issues may arise as the 3D model may not be ready or the project team may not be confident in presenting them to public stakeholders.

The best solution for most architects and developers is to decide on focused design decisions needed in the building project. Creating a model that best reflects the fundamental requirements of the building project, while also presenting room for the design to evolve and grow, will help external stakeholders identify what parts of the design being presented is for informing and what is being currently decided upon, in which they can aid with insight

Benefits of 3D Models in Public Participation

Nevertheless, the 3D model is an enticing prospect as it encourages public participation. The Warrington example presents a public engaged with the designs of a building project which would be central to citizen’s daily life.

Fundamentally, the participants were able to recognise and comment on an aspect of the design which was never picked up on within the master plan. Recognising the area’s importance and functionality with its population is important for community engagement because it presents the environment's social use. Something, which becomes more important as the high street changes, and our society develops its social environment.

When relying on 2D images in survey tools, there can be just as much bias (feared) in 3D models as it focuses primarily on a single piece of information. Using a 3D model opens participants to view the building project within its future environment and while participants can recognise some areas of a plan, they still rely on secondary information. This can be time consuming within the public consultation when only so much time is allotted for the public to engage with the architect and planner.

By designing information that non-professionals can understand, 3D models help members of the public engage more intuitively. This might be a simple change but it drastically alters the relationship between stakeholders, as less time is being occupied by the public trying to comprehend the information being given by the consultation.

Conclusion

The 3D model has the potential to drastically change the public consultation, as it reinvigorates the conversation between a building projects team and external stakeholders (public.) The UK has a rich history of developing its planning policy to include an aspect of social engagement when discussing the shared environment.

In this article we engage with a 3D model being currently used as a public consultation tool in the UK, and the concerns and benefits that have emerged. While a 3D model requires time and expertise within a building projects timeline, sometimes this effort can fall short when reviewed by the public, and aspects of a design can be misread and undervalued.

Nevertheless, the engagement with the public is reinvigorated. The citizen can more easily understand projects through recognisable visual information, and therefore be able to participate in the day-to-day democracy of their environment.

While the developer may be concerned by the implications of the 3D model, they are currently looking towards more digital tools to engage with external audiences. As the UK Government addresses the need for more immersive technology in different aspects of governance and economy – it might be in the interest of the developer to stand out from the sea of social media with a tool that presents the company as transparent.

Speak to us about the power of interactive 3D models for your next planning consultation!

About Megan

In conjunction with PlaceChangers Ltd., Megan Marie Doherty completed an industry-sponsored PhD at Northumbria University on the ‘Design and Evaluation of Building Information Modelling capabilities for public consultation in urban planning and master planning’. Megan Doherty has a background in public engagement from previous roles in media and heritage organisations.

You can follow her on Twitter: @m3ganmdoherty